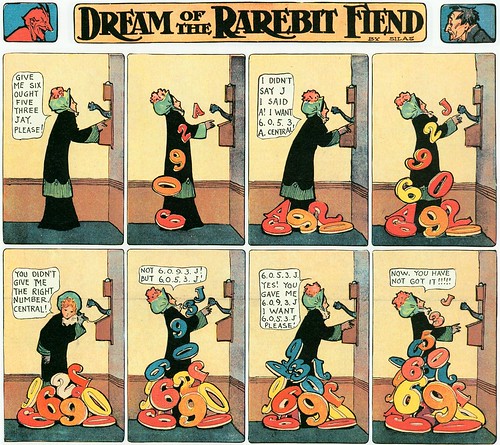

Designing may include dreams or obsessions. A century ago, hundreds of visualized dreams appeared as stories in strip form, in American newspapers, titled ‘Dream of the Rarebit Fiend’. Strips made by an author who called himself SILAS. On the stunning 2007 reissue of these dreams, in the form of a book + DVD by German collector Ulrich Merkl, Dutch pictureanalyst and designer Huib van Opstal now gives the following analysis.

Capsule Bio

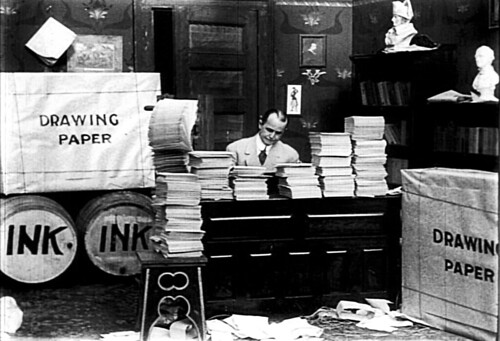

Artist-writer Winsor McCay posing and looking his sharpest.

Winsor McCay’s strips were about obsessions. A boy’s obsessive urge to sneeze! A girl’s obsessive urge to eat! A man’s obsessive attempts to get rid of his ‘dull care’ valise! But… his greatest obsession proved to be dreaming. First, his strip series ‘Dream of the Rarebit Fiend’ (1904-1913, in black-and-white), which was about addicts of Welsh rarebit, a heady dish of melted cheese over toast — which could give one the weirdest of dreams. Second, his strip series ‘Little Nemo in Slumberland’ (1905-1911, in dazzling full color), this time specifically about a child dreaming. My shortest possible profile of the man behind the pseudonym ‘Silas’ is the following. American artist-writer Winsor McCay lived from 1867 to 1934. He did everything single-handedly, with drawing board and ink bottle as his ball and chain; a baffling human dynamo, obsessed with obsessive behavior. He left us weird and wonderful strips and cartoons, of which the strips under his pen name SILAS were among the earliest for adult readers. His forte was the dreamstrip, full of realism and surrealism…

Winsor McCay at work in the live-action prologue of ‘Little Nemo’, his first animated film (1911).

Life & Career

A dreamer wakes up a true believer (#617, July 6, 1913, final panel).

Drawing day and night in develish detail proved to be his lifelong therapy. Being an eager artist-reporter from the start, McCay later stated: ‘…I couldn’t stop drawing anything and everything!…’ From the late 1880s on, he got paid for showing his observational skills in public, making sketches, large-sized posters and billboards for freaky traveling circuses and dime museums. Likewise eccentric was his elopement and marriage, in the early 1890s, with a ten years younger teenage bride, of barely fourteen, who bore him a son and a daughter. (In 1898, his brother Arthur landed in an insane asylum, for good, at thirty. In 1903, McCay himself began publishing strips, at thirty-five. In 1910, his sister Mae was dead, at thirty-three. And in 1914, he more or less drew his last strip, at forty-six. Neither his brother nor his sister he ever mentioned to anybody.) He chose making newspaper strips within deadlines, the heaviest task imaginable. ‘…WORK! WORK! That’s all there is to cartooning…’ He was a lifelong member of the secret order of Freemasonry, always went impeccably overdressed, hat and all, and obsessively loved looking sharp. He died at sixty-six.

Craft

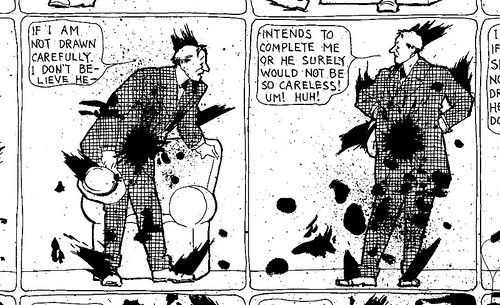

What really perfected his visual skills, was working at a large printing and engraving firm, and seeing his work appear in print, in journals and magazines, handlettering included. Large-sized, small-sized, in the 1890s he mastered it all. Although he suggested grey areas by hatching or cross-hatching in thin pen lines, his personal style of pen and ink drawing was done in black ink in so-called ‘line art’, composed of solid lines and areas only, with no gradation of tone. ‘…The fewer the lines the harder the work…’

Gradually being destroyed by ink blots, a character talks to his creator (#277, March 30, 1907).

From 1903 on, a large part of his work was also reproduced in full-color printing. From the start his strips on paper were impressive, full of truly cinematic techniques which had barely reached cinema itself. Comic interrelationships shown in split-screen, close-up, morphing, panning. American urban landscapes. Often grand perspectives and panoramas in almost photographic detail. From 1903 to 1914, McCay produced many enjoyable stories in strip form, full of the utmost realism as well as surrealism, fantasy, humor and wordplay, and full of autobiographical detail too, published nationwide. He then quit the strip medium abruptly — and for the rest of his life exclusively produced a stream of fantastically drawn, but overly moralistic editorial cartoons. In the mid-1920s, a two-year comeback attempt as a comic strip artist proved unsuccessful.

Filmmaker

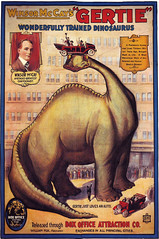

Poster for Winsor McCay’s third animated film, ‘Gertie the Dinosaur’ (1914).

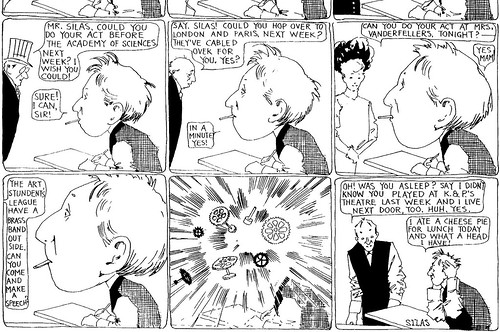

Meanwhile, in his spare time, when animation had only just left its flipbook stage, he made some self-financed pioneering animated cartoons which still involved making each and every in-between drawing — 24 per second! — each on a new sheet of paper. Jokingly, in the live-action prologue of his first animated film in 1911, he suggested barrels of ink and enormous piles of paper were needed, which wasn’t far from the truth. His 1914 short animated film ‘Gertie the Dinosaur’ was still a ‘silent’ film, with handlettered written dialogue texts or captions between the scenes, long before sound film existed. And it also had a live-action prologue in which McCay himself was the star. An effect he playfully enlarged upon in his live theater performances, by talking to the screen and having his moving picture ‘react’ to what he said. As no one else he himself knew how fast a draftsman he was, thus, from 1906 to the 1920s, as a family entertainer he was a headliner in vaudeville theaters, performing with his ‘lightning sketch’ act and projecting his own animated films. His newspaper work he did backstage between shows, or late at night in his hotel room. Regularly appearing in his own strips, one day, being smothered with praise for his stage appearance, Silas’s head exploded (#241).

Smothered with praise for his stage appearances, Silas’s head explodes (#241, November 22, 1906).

Freud & Silas

McCay’s strips were about obsessions. In 1904-1906, for 90 weekly episodes: ‘Little Sammy Sneeze’, about a boy’s obsessive urge to sneeze. In 1905, for 27 episodes: ‘The Story of Hungry Henrietta’, about a girl’s obsessive urge to eat. (Sammy and Henrietta even met, in a crossover strip.) In 1905-1910, for 150 episodes: ‘A Pilgrim’s Progress’, about a man’s obsessive attempts to get rid of his ‘dull care’ valise.

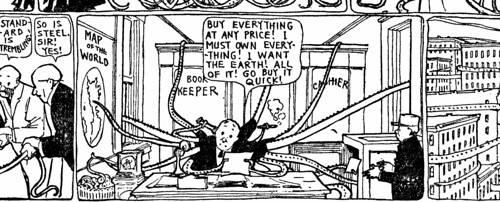

A businessman who wants to own everything turns into an octopus, in 1908 (#452).

Dreams

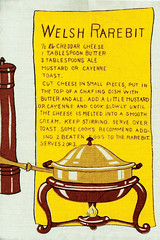

The chafing dish in which Welsh rarebit is prepared. A heady dish of melted cheese over toast, similar to cheese fondue.

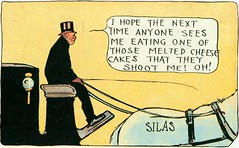

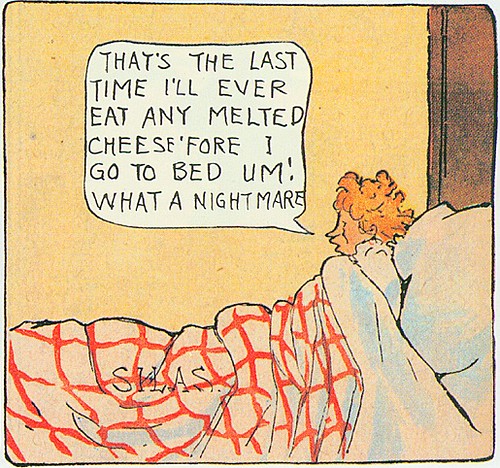

But, McCay’s greatest obsession proved to be dreaming… In 1900, Sigmund Freud’s book ‘The Interpretation of Dreams’ appeared, and proved to be a best seller. Then, the American newspapers offered weird dreams by someone who called himself ‘SILAS’, in a long strip series with the cryptical title ‘Dream of the Rarebit Fiend’ (published from September 1904 to 1913). Behind the name Silas was Winsor McCay. The word ‘fiend’, meaning ‘enemy’ or ‘evil demon’, is of Germanic origin: the Dutch ‘vijand’, and the German ‘Feind’. For McCay this was funny enough, he soon illustrated a two-way title above his strip episodes, with both a grinning devil and an astounded dreamer. All because a ‘fiend’ is also an addict, in this case one which is excessively fond of Welsh rarebit, a heady dish of melted cheese over toast, a dish similar to cheese fondue — which could give one the weirdest of dreams.

Pen Name

This Rarebit strip appeared mainly in black-and-white episodes. McCay made it under his nom de plume Silas, which was a near anagram of ‘alias’, one he needed for contractual reasons. (The only strip he ever did under a fictitious name.) Winsor McCay was born as Zenas Winsor McKay. He never used the first name Zenas, and at first signed his work only with his shortened version ‘Winsor Mc’, just to avoid choosing between the K or the C. All because, in the 1890s, his father for some reason had made the switch from McKay to McCay. In the end, finally signing exclusively with ‘Winsor McCay’, from 1904 on, he remained a specialist in ‘fabrications of Barnumesque proportions’. In his life as well as in his strips. (According to its posters since 1891, Barnum & Bailey was the American traveling circus that gave ‘The Greatest Show on Earth’.)

Little Nemo

A year later — when 113 episodes of his Rarebit strip had already appeared — McCay started a second dreamstrip, this time a series of strips about a child dreaming. It was to become his best-known work, titled Little Nemo in Slumberland, (published from mid-October 1905 to 1911). Probably to make it more suitable for reading aloud to children, during a period of five months he added extra captions under the panels with speech balloons. (All text in his strips he always handlettered, in capitals.) Published in weekly episodes, in dazzling full color in the comic sections of Sunday newspapers, nationwide. Sections with huge pages, measuring half a meter high.

Color

Only 29 Rarebit episodes appeared in color, this is from one of them (#601, March 16, 1913).

Already early on, his drawing teacher, John Goodison, taught him about stained glass, the colored glass medium closely resembling McCay’s colored strip drawings: with thick black outlines around fields of color, and with stories told in rows of panels. A little boy by the name of Nemo had colorful fairy-tale dreams, from which he always woke up in the last panel of each episode. Often stories with stunning visual effects, with some vague continuity from week to week, but storywise going rather nowhere, which is why they’ve been aptly labelled ‘non-stories’ by historian Alfredo Castelli. ‘Little Nemo’ was published in the heyday of trick films and Féeries, of which it was a printed strip version. Nemo, in Latin meaning ‘no one’, was a strip character that also resulted in spin-off merchandising, two short silent films (a 1906 live-action trick film and a 1911 animated cartoon), and a 1908 Broadway musical included.

Rarebit Technique

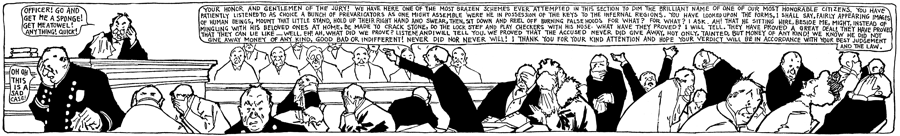

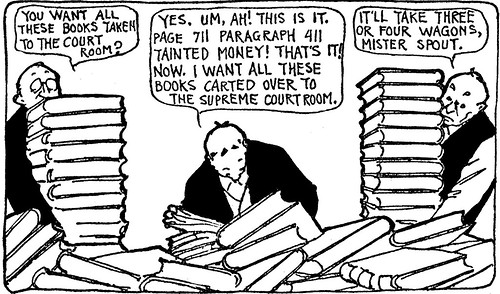

His Rarebit strip of 1904-1913 consisted of truly modern observations. Everyday actualities, and everyday dreams and dramas — especially adult ones. From daydream to nightdream, nightmare or night terror. Many a dream was started by someone reading: a journal, a letter, a label, a card. The dreamer always woke up in the last panel of each episode, often still near the Rarebit pan with melted cheese that caused the dream, and could be anyone: husband or wife, baby or granny, tramp or policeman, reader or monkey. The length per episode could stretch to dozens of drawings, the produced number of Rarebit episodes per month could be staggering. (Just in December 1906, a total of 9 appeared for instance, at irregular intervals, with 10 to 24 drawings per episode, all fine episodes, totaling 132 drawings, PLUS the rest of his work that month.) In an age before radio or TV, he had no ear for dialogue. He included wordplay, funny accents and slang, but to him text was just filler. His characters mostly spoke in formalities, quarreled and questioned, or held long cantankerous monologues. Content-wise, most of his text was negligible. (Think of what he could have accomplished working with a better scriptwriter!) Working in pictures-only is what he liked best, but even his meticulous drawing could be sterile. His hand lettering in speech balloons could be erratic, even sloppy. He asked for, and gladly accepted, readers’ ideas for his Rarebit strip, always putting their names in his final panel. Funny enough, in 1906, with the widest and most long-winded speech balloon ever, over a courtroom scene nearly the complete width of the strip, he illustrated endless lawyerspeak with pinpoint accuracy (#174).

Possibly the widest speech balloon ever (#174, April 7, 1906).

Moving Times

A comical fight as pictured a century ago (#56, April 8, 1905).

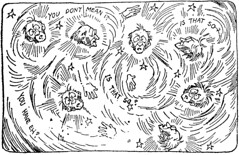

McCay was an early adapter of cinematic techniques, something he did from before the year 1900: shooting angle, point of view, close-up, movement, depth. The order in which he presented scenes in his strips had little to do with ‘montage’ as applied in filmmaking, though. Even in his dream depictions, he stuck to a limited narrative and never departed from the chronology of real time — with masterly results. One of his early Rarebit dreams was about a man being buried alive, as seen through the victim’s own eyes, early in 1905 (#44). From 1906 on, he drew more and more ‘speed lines’ to accentuate rapidly moving objects. In 1911, he pictured the ‘fastest automobile in the world’ in the fastest looking way: with one of its front tires bumping up from the road (#706). In 1908, he pictured a twirling man which three quarters of a century later would be called a ‘breakdancer’ (#456). A comical fight he just drew as heads and shouts whirling round in circles, in 1905 (#56). In the early 1900s, McCay looked backward as well as forward. A range of VIPs of his day were mentioned in his strip, mainly men, and some — like philanthropist Andrew Carnegie — even appeared in it. Blacks he often made fun of, funnyspeak and all. He thought up as much gags about black cannibals as about the early women’s movement and suffragettes. A commuter he drew going home in giant frog leaps, just the way dime novel hero Spring-Heeled Jack and comic book hero Superman moved across the city, decades earlier, and decades later (#390).

Buried alive, as seen through the victim’s own eyes (#44, February 25, 1905).

Moral Code

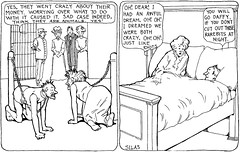

A married couple goes insane after receiving 5 million dollars from Mr. Carnegie (#60, April 22, 1905).

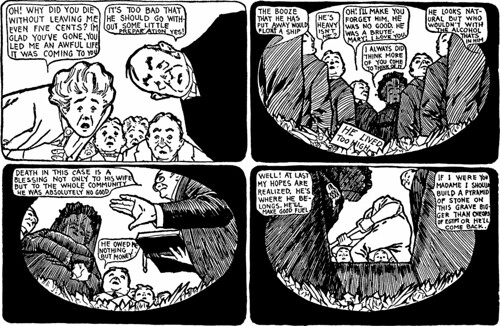

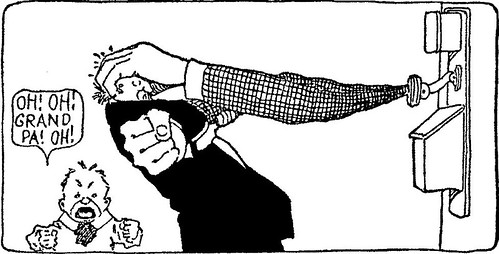

Several times McCay acted in his own strip episodes, always smoking. Addicted chain-smoker himself, he made many of his characters smokers too. Besides, long before the Comics Code Authority ‘seal of approval’ existed, his Rarebit strip did contain many a suicide attempt, plus alcohol abuse, euthanasia, insanity, death, blood, and offensive violence (as for instance a man mistreating everybody including his grandmother he mercilessly threw out of a window, #211). His characters broke out of his panel frames quite often but their maker ruled: with pen or eraser in hand he could make or break them (#517).

Complaining to boxer James Jeffries, a man is attacked through the phone (#152, February 15, 1906).

Sound Technique

All modern themes seem to be there in these vintage strips, in often surrealistic varieties. The plots were mainly about adults lost in the big city jungle, clearly in need of better signage. In his days, electricity, the photographic camera and the telephone were already as common as they are now. He made fun of a salesman in prehistoric times who kept his accounts on stone tablets (#304), and of a reader in modern times needing a horse to inspect his ‘library of millions of books’ (#370). Plus early cosmetic surgery (#98), hair transplant (#597), genetic engineering (#652) — or of a jealous ‘comic artist’ by the name of Mr. Penline who assembled or disassembled his beautiful young wife to his liking (#302).

A man commutes in his own flying machine (#563, 1910).

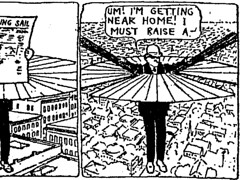

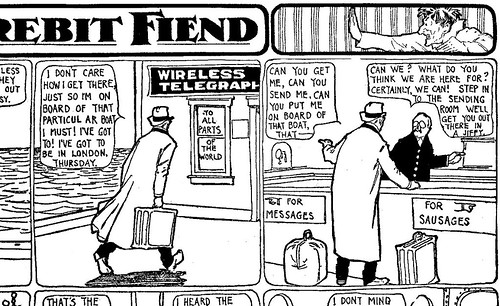

The picture he gave of his times, was lightly anachronistic as well as futuristic, ranging from airships and airplanes to a car to ride underground — ‘a cross between an Auto-Mole and a Sub-Terino’ (#544), a movable house (#692), a baseball circling the earth (#411), a commuter’s flying contraption to drift home by the wind (#563), and a complete man sent by wire (#189). Santa Claus’ reindeers and sleigh gliding out of a living room wall, closely resembled what we now call virtual-reality projection (#548). In 1906 he had a character cryptically curse in asterisks and x-es (#157). In 1909 he pictured sound effects like ‘TUC TUC TUC’ (by an outboard motor, #520), ‘KNOCK KNOCK’ (on a door, #535) or ‘ZING’ (by a telephone, #572). In the very first Rarebit episode, of September 10, 1904, he already lettered a speech balloon with an oversized ‘YES’.

A businessman missing his boat is wired aboard wireless, using a ‘seperator and grinding machine‘ (#189, May 19, 1906).

Before & After McCay

The last two centuries, pictorial storytelling in print has really began to evolve, thanks to the rapid development of new reproduction and printing techniques. (Believe it or not, but much of its history is still being unwritten today.) The work of British caricaturists like James Gillray and George Cruikshank — in which framing and speech balloons were present from day one — paved the way. Swiss and German artist-writers like Töpffer and Busch further popularized the form. In America the strip story peaked abundantly in Wild Oats magazine, in the 1870s, with early stories by Frank Bellew, Palmer Cox, Livingston Hopkins, Frederick Opper and others. Decades later, the medium of the printed strip on paper really came to the fore, in the mid-1890s, when the age of ‘yellow journalism’ began, with full-page full-color strips, in poster-sized American newspaper sections — making R.F. Outcault’s ‘Yellow Kid’ strip famous in the process. (But DO forget a tag like ‘the first comic strip that came into existence’, which is nonsense.) Many great talents have emerged since then, of which Winsor McCay is just one example. And many different labels, ranging from ‘comic strip’ to ‘sequential art’, have been put on the form since.

Inspiration

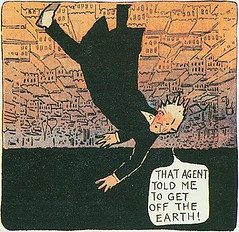

A man who considers himself to be a theatre star, falls off the turning earth (#600, March 9, 1913). ‘…McCay laid the groundwork & climate (…) & was largely ignored…’

It was in the 1960s, when renewed interest in the history of popular media surfaced, that the bug hit me. Early in 1969, Canadian publisher George Henderson sent me his reprint-paper Comic World (with a.o. a special issue titled ‘The Magic of Winsor McCay’), and issues of his Captain George’s Whizzbang — in which B.P. Nichol stated: ‘…McCay laid the groundwork & climate (…) & was largely ignored…’ (Especially for the Rarebit Fiend strip, this has certainly been the case.) From 1970 on, a giant oversized Little Nemo poster hung above my desk: McCay’s full-color Sunday episode of August 12, 1906. And, in 1972, as a young Dutch student I got permission to spend my grand tour in the United States, solely to find out more about popular media. One of the highlights there was seeing bald-headed collector Bill Blackbeard (45 years young) and his San Francisco Academy of Comic Art (SFACA) archive. Still in his own home then, stacked from top to bottom with vintage newspaper strips. Without his emergency plan of action in the 1960s, saving piles and piles of brittle old American newspapers from destruction, we would now know even less of the history of the strip medium. For me, leafing through his original Sunday newspapers, mostly bound and in thick volumes, dating back to the turn of the century then, was an inspirational high point. The Kid!… Nemo!… Krazy!… Moon!… Polly!… Annie!… Wash!… Popeye!… Screwloose!…

Copycat Authors

The man behind the 2007 Rarebit Fiend reissue — and also its researcher, restorer, uncensored writer and picture editor, annotator, bibliographer, private publisher — is German collector Ulrich Merkl, born in 1965, a scholar who ‘…spent six years as a house husband raising two children and writing the present book…’ For the occasion, he wrote it in British English. Merkl’s McCay book had, due to its large size, to be printed and handbound in Egypt, where he personally inspected his brainchild at the printing press. Winsor McCay’s creative outburst from the early 1900s may long have been ignored by the reading public, but it has certainly become a great inspiration to many other copycat authors. To avoid using nastier words like ‘stealing’ or ‘thieving’, Ulrich Merkl labels the phenomenon of authors-copying-earlier-authors politely as ‘possible quotations’. The use of a euphemism, as I did likewise years ago with my label ‘picture rhyme’ (‘beeldrijm’ in Dutch) in my 1994 biography ‘Essay RG’. My own book on another similarly great double talent influenced by a multitude of earlier creators — Tintin creator Hergé, from Belgium, who lived from 1907 to 1983. And a publishing project identical to the Rarebit production: I was my own researcher, restorer, uncensored writer and picture editor, annotator, bibliographer and private publisher too. It took me fourteen years to make, from start to finish. So stunning was the amount of reused sources in the strips of Hergé, that ‘The Thief of Brussels’ was one of the latest working titles for my book, one I fortunately changed, just in time, into something less offensive. Because, reusing ideas can mean moving forward or making improvements, which was often the case with Hergé.

Compare

A man’s anger over the cost of his wife’s new hat turns him into a human torch (#400, 1908).

In Ulrich Merkl’s book, in the case of Silas’s copycats, do enjoy comparing visuals from well-known films (like ‘L’Age d’Or’, ‘King Kong’, ‘Dumbo’, ‘Mary Poppins’, ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’ and ‘Mr. Flubber’), or visuals from well-known strips (like ‘Plastic Man’, ‘The Human Torch’ and ‘Uncle Scrooge’). Together forming a true gallery of greats: filmmakers and stripmakers like Tex Avery, Carl Barks, Luis Buñuel, Jack Cole, Salvador Dali and Walt Disney. Not forgetting some great creators in other fields, like pulp fiction, photography or pop art. Without a doubt, McCay himself did know the works of many earlier creators. An illustrated essay by scholar Alfredo Castelli for instance shows predecessors who made dreamstrips before McCay. Besides, the quality of graphic artists in the 1800s, before the arrival of the motion picture, was truly awesome and inspirational too. Oberländer!… Frost!… Kemble!… Caran d’Ache!… — and so many others. Comparing the works of great pictorial artists and storytellers, considerations like ‘strip’ or ‘no strip’ just turn out to be unimportant. Storytelling can be done in many forms for shelf and screen.

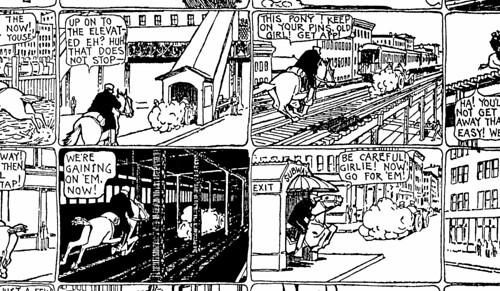

A 1907 mounted cop chasing a speeding car across New York City closely resembles a 1971 movie, ‘The French Connection’, and a 1994 movie, ‘True Lies’. (#314, August 10, 1907).

Pop-Eyed

Eyeballs popped out in a hip Rarebit page in 1906 (#176), and eyeballs popped out in a hip ‘Big Daddy’ Ed Roth drawing from the 1960s. It probably does not make McCay the inventor of this gag though. My experience is that ideas go back like falling dominoes. Ideas are often like ticks in a row. Two examples showing close resemblances for instance, are probably just a link in a chain which, no doubt, and in due time, will prove to be much, much longer. Take a crazed mounted cop chase through New York for instance (Rarebit #314, 1907), and compare it with a 1971 movie, ‘The French Connection’, and a 1994 movie, ‘True Lies’. Ideas can go way back, and can easily circle the world. For example, when Winsor McCay published his Rarebit episode #211, in 1906 (the one solely filled with offensive violence), the Spaniards Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali respectively were only six and two years young. Uncontestedly, their 1930 surrealistic short film ‘L’Age d’Or’, was scripted from A to Z from Winsor McCay’s Rarebit episode. American newspapers reached Spain too, an early Spanish Blackbeard may have saved the strips in them. There’s plenty of work to do for researchers the world over. McCay’s work was, and still is, an inspiration to many.

Ulrich Merkl scanned complete newspaper archives digitally, a 1906 law student had to check his archival library manually (#174, April 7, 1906).

2007 Book + DVD

‘Dream of the Rarebit Fiend’ was a pioneering series for adult readers from the early 1900s, full of contemporary history. Now, history is bound to repeat itself, in this glorious production by Ulrich Merkl, from Germany. For me, his Rarebit book + DVD proved to be THE brainstorm of the century. At last, all known strip episodes of Winsor McCay’s dream interpretations (821 of them, chronologically numbered by Merkl) are on our shelf and on our screen. Hundreds of these episodes have never seen a reissue before. During his lifetime, Winsor McCay himself saw only one Rarebit book appear, in 1905. (His popular ‘Little Nemo’ color newspaper strip he never saw in bookform — it was just TOO large in size, then.) His Rarebit black-and-white strip was published nationwide, but scattered and in different formats, mostly in a newspaper here, a newspaper there, and often just for short intervals. The papers put it in their pages under the label ‘humor’ — which was thin in McCay’s Rarebit strip. Perhaps its contents was seen by editors and publishers as too nightmarish, too adult, not sweet enough.

Extras

A dreamer wakes up with a death wish (#604, April 6, 1913, final panel).

Merkl’s book is 464 pages thick, hardbound, with an added DVD in its inside back cover. It has a nifty red reading ribbon, is oblong-sized, weighs no less than 4.3 kilograms, and opened flat measures 88 centimeters wide. It opens with explanatory notes and chapters by Ulrich Merkl plus essays by two more scholars. It has well over a thousand illustrations, of which 219 are in color. Each episode or illustration has its caption plus footnotelike annotation where it works best: right with it. The visuals came from three sources: original artwork, brittle old newspaper volumes and microfilm. Only the microfilms were complete; they proved invaluable for dating individual episodes. For picture quality they often proved to be worthless, a lot of retouching had to be done. About half of the Rarebit episodes have been put in the book (excluding the ones in color), plus, all 821 of them have been made digitally available on the DVD, in hi-res (and including the 29 in full color, #593 to #621 & #813). The DVD has even more extras: the complete text of the book, a descriptive catalogue with longer annotations than in the book itself, and a clip from an animated cartoon by McCay.

Availability & Links

Of this spectacular eye-opening book + DVD production, only a limited edition of thousand copies was made. It can be purchased directly from Merkl in Germany, who sends it terrifically well packed, by surface mail. The price lies around 89 euros per copy + shipping costs, see the details on his Web site.

McCay’s logo for the widest episodes of his Rarebit Fiend strip.

2007, Ulrich Merkl, ‘The complete Dream of the Rarebit Fiend (1904-1913) by Winsor McCay ‘Silas’; With contributions by Alfredo Castelli & Jeremy Taylor’, Hohenstein-Ernstthal (Germany): Ulrich Merkl, in English, introduction, chronology, essays, text sources, strip episodes, 1000+ illustrations in b/w & fc, annotations, bibliography, 464 pages, oblong, size 43 x 31 x 3 cm, hardbound with red reading ribbon; with inserted DVD containing all 800+ dreams in hi-res and the complete text with more exhaustive notes, historic dossiers, and an animated cartoon clip; book + DVD design by Beduinenzelt; ISBN 978-3-00-020751-8

A dreamer finally wakes up (#598, February 23, 1913, final panel). What a nightmare!